As with many industries, the lubricant and base oils industries were and continue to be buffeted by the COVID-19 pandemic—from a large drop in demand to supply chain disruptions, transportation shortages and increases in costs. One of the biggest impacts was an unprecedented run-up in base oil prices, a development that encompassed all grades in all regions.

Like a gigantic pendulum, price tags on the industry’s far-biggest raw material began with a brief backward swing, then went on a year-long climb, reaching historic levels. Then they reached a plateau where they’ve hovered for the past seven months.

All eyes are watching to see what happens next. With the pandemic perhaps ebbing, some predict the pendulum for base oils will swing toward surplus capacity and tighter profit margins, pressuring some producers to exit the market even as new capacity continues to enter.

Base oil suppliers braced for disruptions as COVID-19 made an appearance in late 2019. Those were realized by March when large numbers of cases plagued most of the globe. Governments imposed severe lockdown measures early on, drastically curtailing some types of transportation—especially personal use of automobiles and air travel. At the same time, numerous types of businesses temporarily closed or cut back on operations, most in conformance with government policies but some due to decreased business. The upshot was a sudden decrease in demand for automotive and industrial lubricants—and therefore base oils.

Demand for transportation fuels fell even more drastically, creating two shocks for base oil markets. The most immediate was an unprecedented fall in crude oil prices. The drop in fuels demand slammed the brakes on products coming from the back end of refineries, but the supply chain gives much momentum to crude oil and other feedstocks coming in the front end. Refiners produced significantly more product than they could sell and quickly ran out of room to store the excess. To avoid being overwhelmed, they cut prices and in some cases paid to have material taken away. West Texas Intermediate crude oil futures dropped below zero and traded as low as minus $37.63 per barrel on April 20.

Crude quickly moved back into the black, but refiners had to take drastic action that caused the second shock. Around the world, oil companies cut back sharply on fuel refinery operating rates. In some cases they temporarily closed facilities; in others they throttled operations to significantly less than full capacity. In the United States, which has the world’s largest oil refining base, utilization rates dove below 70% in April 2020.

As is often the case, these actions were driven by considerations for fuels—the highest volume product from refineries. The actions affected other products, including base oils. Less crude throughput meant less production of vacuum gasoil and other feedstocks, placing a cap on base oil production capability.

Partly because of base oil inventories and partly because base oil demand had dipped, it took some time for the effects of less base oil production to bubble to the surface. As inventories were drawn down and lubricant demand began to recover, shortages developed that spread around the globe and became increasingly severe over the next year. Other factors also made impacts. The biggest may have come from arctic storm Uri, which struck Texas in February 2021. It temporarily closed several refineries along the U.S. Gulf coast, causing a loss of capacity exceeding 5 million barrels per day.

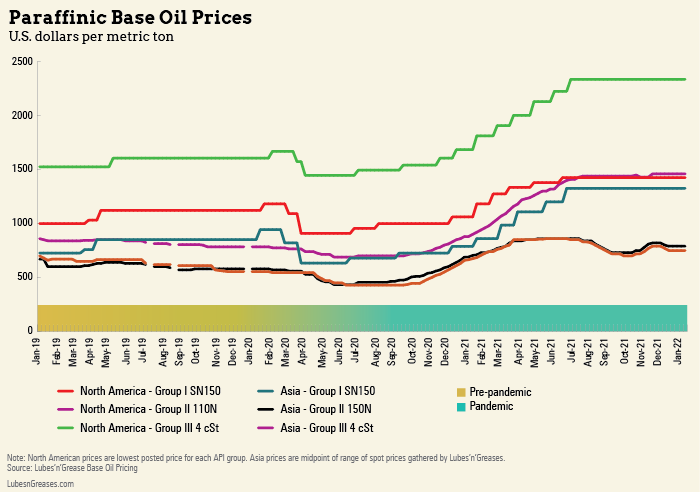

The result was unprecedented volatility in base oil prices. Initially values fell sharply in tandem with crude oil. According to Lubes’n’Greases Base Oil Pricing Data, in mid-February 2020 the lowest posted price in North America for API Group I solvent neutral 150 was $1,183 per metric ton while the lowest postings for Group II 110 neutral and Group III 4 centiStoke were $944/t and $1,670/t, respectively. By early April, each had fallen between $223/t and $310/t.

At mid-year all grades began a gradual climb that brought them back to March 2020 levels by January 2021. By the start of 2021, though, shortages had become clearly evident, and they continued to worsen, causing the run-up to accelerate sharply. The first half of the year saw five rounds of hikes for North American postings. At that point the lowest Group I value had increased 56% from the low point just over a year earlier. Group III had risen 62%, and Group II 90%.

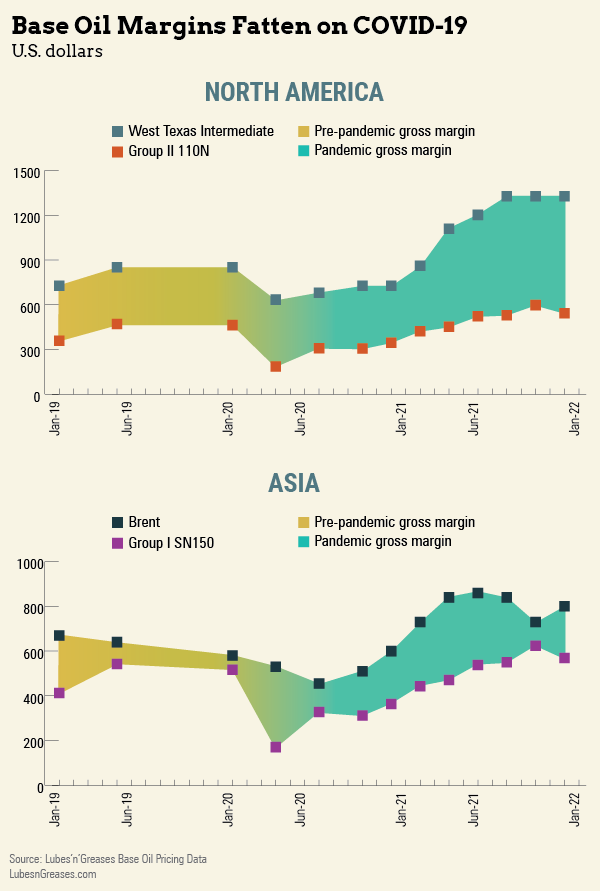

Crude costs remained in the same neighborhood where they’d been in 2019, so much of the increase was reflected in gross margins—the difference between base oil and crude prices and a rough indicator of base oil profitability. From the start of 2020 to mid-2021, the gross margin for the lowest North American Group II 150N more than doubled from $388/t to $798/t.

Base oil prices around the world vary significantly, but other regions followed the same pattern. North America is the only region where base oil producers post prices, but in Asia values for spot sales of Group I, II and III fell between 10% and 22% in April and May, then rose between 74% and 112% by November 2021. Group II margins jumped 245% from the start of 2020 to mid-2021.

The price swings were wildest in Europe, where spot prices for Group II 150N sold within the region and Group I SN150 exported from the region fell about 40% in April 2020, then more than tripled by mid-2021. Group II margins swelled more than three-fold from the start of 2020 to the middle of 2021, while those for Group I exports rose more than five-fold.

“The price increases that we saw during the first year and a half of the pandemic were remarkable and may have been unprecedented,” said Joe Rousmaniere, a long-time participant in the base oil industry. “Margins were also exceptional. That’s what happens when you develop a big shortage. Refiners couldn’t make enough base oil, but on the barrels they did sell they made very good money.”

In the third quarter, the run-up stalled. From autumn through January, values for all grades in all regions plateaued or retreated. Refiners had gradually ramped up operations during the last eight months of 2020. U.S. utilization rates were still significantly below average pre-COVID levels at the start of 2021 and briefly crashed below 60% during Texas’ cold spell. They climbed to the upper 80s by June and have mostly remained in that range since.

“Since the start of the pandemic, we’d seen major decreases in refinery utilization related to weak transportation fuels demand,” said Lance Puckett, president of Ergon Refining Inc. and Ergon–West Virginia Inc. “Now we see base oil production catching back up as refinery utilization has increased and more stable operations have resumed. This is apparent in the price of many base oil products softening over the past several months.”

Gerald Heaton, director of consulting firm Elementalle, concurred. “Refinery run rates gradually increased, resulting in more [vacuum gasoil] availability, so base oil supply improved, closing the supply-demand tightness and tension that had existed. The 1-0-1 of market economics occurred with price stabilization first, and then some price declines.”

Now the question is whether the pricing pendulum is preparing to swing back in the other direction. That depends partly on whether the crisis wanes. At the time of writing, COVID continued to rage, but some healthcare experts were predicting that numbers of new infections would plummet in coming months. Many in the base oil industry are anticipating the market’s return to normal.

The outcome for base oils may depend much on what happens to economies as well as fuel and lubricant demand. Some economists worry that the world could experience a hard landing as governments withdraw the fiscal stimulus that has buoyed economies during the crisis.

Nevertheless, many argue that the best base oil barometer in the long run is the balance between demand and production capacity. Market insiders and analysts agree it makes more sense to talk in terms of base oil margins rather than prices. Prices have historically depended largely on crude and feedstock costs, and the strength of that link may be restored in the absence of feedstock shortages. Many agree that crude prices are nearly impossible to predict and that it is as difficult to forecast whether base oils will rise or fall. It’s easier, they contend, to predict whether base oil margins will narrow or widen.

Attention is turning to the balance between capacity and demand and the impact it had on margins before the pandemic. For years leading up to the pandemic, the world had a chronic surplus of base oil capacity that grew steadily, compressing margins. Since the pandemic started, that imbalance has worsened. Refiners shuttered several plants and set schedules to close others. The combined capacity of those facilities is 1.1 million t/y. That number was more than offset, however, by two expansions in China and a third in Spain, which added 1.4 million t/y of capacity during the pandemic.

Moreover, seven projects in China, India and Russia are scheduled to be completed by the end of 2022 with combined capacity of 2.3 million t/y. In 2021 worldwide base oil capacity totaled 63 million t/y, according to Lubes’n’Greases Base Stock Plant Data, versus pre-pandemic base oil demand of roughly 40 million t/y.

“The market really has shut down very little capacity, and it keeps adding new capacity,” said Stephen Ames, principal of SBA Consulting. “Demand is not increasing; demand is falling. So as things get back to normal we are going to be right back where we were in terms of surplus capacity. In fact, we’ll have even more of a surplus. So margins are going to be rotten.”

Base Oil Capacity Changes During Pandemic

| Company | Location | Status | Capacity | Date | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtractions | ||||||||

| Galp | Matosinhos, Portugal | Closed | 150,000 t/y Group I | Early 2021 | ||||

| TotalEnergies | Gonfreville, France | Closed | 289,000 t/y Group ?1 | 2021 | ||||

| Shell | Pulau Bukom, Singapore | Closing | 386,000 t/y Group I | Due to close 2022 | ||||

| Additions | ||||||||

| Eneos | Negishi, Japan | Closing | 229,000 t/y Group I | Due to close 2022 | ||||

| Handi Sunshine Petrochemical | Hainan | Expansion | 400,000 t/y Group II/III | May 2021 | ||||

| SK-Repsol | Cartagena, Spain | Expansion | 194,000 t/y Group II/III | July 2021 | ||||

| Qinghe Petrochemical | Zibo, China | Expansion | 800,000 t/y Group II | 2021 | ||||

| Shengdong Petrochemical | Lianyungang, China | New plant | 700,000 t/y Group III | Due in 2021; no announcement yet | ||||

| Feitian Petrochemical | Xinji, China | Expansion | 250,000 t/y Group II | Due in 2022 | ||||

| Hindustan Petroleum | Mumbai, India | Expansion | 150,000 t/y Group II/III | Due in 2020; no announcement yet | ||||

| Bharat Petroleum | Mumbai, India | Expansion | 450,000 t/y Group II/III | Due in 2022 | ||||

| Gazprom | Omsk, Russia | Expansion | 220,000 t/y Group II | Due in 2022 | ||||

| Indian Oil | Haldia, India | Expansion | 270,000 t/y Group II | Due in 2022 | ||||

| Rosneft | Novo-Kuibyshev, Russia | Upgrade | 250,000 t/y Group II | Due in 2022 | ||||

Some think the outlook for suppliers is less dire—or less certain. Dale Fatland, U.S. vice president of procurement for Schutz Specialties and Lubricants, said it’s possible that the price run-up still has legs.

“In November and December, prices plateaued but only because that was the slow time of the year, although November was relatively strong,” he said. “Prices have been bouncing around too much, and we have not seen a solid trend so far, but we will have to wait to see what happens in January. I don’t expect the market to be flooded with product, but if people are driving less, or not driving to the office, the market will be a bit long.”

Fatland also predicted that the shortages encountered during the pandemic will cause buyers to purchase larger volumes under contract and suppliers to carry more inventory. If true, those factors could help soak up supply for a time.

If the squeeze on margins resumes, analysts say it won’t press evenly on all grades. Demand from lubricants continues a decades-long trend shifting from Group I to Group II and III grades, so low- and medium-viscosity Group I oils would feel the press most. Bright stocks are the exception among Group I grades, as the loss of Group I plants has made them somewhat of a premium product, along with petroleum wax.

“Group IIs have an advantage because they are considerably less expensive to produce than Group I,” Ames said. Some insiders expect Group III grades to retain their margins best due to growing demand from passenger car motor oils. Ames noted, though, that refiners in China and India are adding new capacity.

Most analysts do not expect demand growth to absorb the surplus. Finished lube consumption may still be expanding in developing economies, but for years it has been basically flat in the U.S. and shrinking in Europe, keeping global growth in the low single digits. A more likely way for the surplus to significantly diminish is for base oil plants to close. For years leading up to the pandemic analysts predicted that plants would shutter for this reason. A few did, but never constituting as much output as analysts said was necessary to reduce the surplus.

There seems to be wide opinion that base oil profits made during the pandemic are not sustainable with today’s capacity surplus once feedstock constraints cease.

“The past two years were a very profitable time to be in the base oil business,” Rousmaniere said. “If refinery operating rates return to normal levels, though, base oils are going to be back to baseline, which means a large surplus of capacity. In fact, the surplus is getting bigger. In the long run that means margins are going to go down, and things will be a lot tighter—at least until something happens to reduce the surplus.”

Read more from our Special Report: Base Oils Emerge from Pandemic:

• As the Pendulum Swings – The COVID-19 pandemic led to sharp changes in base oil pricing and margins. Will the market settle into a new post-pandemic norm, and what might that look like?

• Base Oil Rerefiners Rebounding from Pandemic – The pandemic wreaked havoc on the base oil market, but rerefiners may have emerged stronger than ever.

• China Moves to the Top of the Heap – China overtook the United States in 2021 as the country with the most base oil refining capacity. What contributed to its rise?

Gabriela Wheeler is base oil editor for Lubes’n’Greases. Contact her at Gabriela@LubesnGreases.com

Tim Sullivan is base oil executive editor for Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Tim@LubesnGreases.com