It’s nothing new for industry to bristle at the burden of regulation. For decades governments have created rules for businesses to follow, and businesses have complained or warned about the impacts on their operations—and in some cases about ultimate impacts on individuals and society.

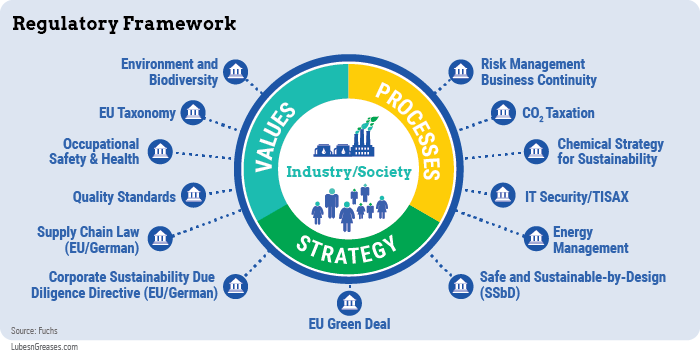

But alarms an order of magnitude greater are currently going up in Europe about a network of regulations that is even larger. Adopted in 2020, the EU Green Deal is the European Union’s incredibly wide-ranging attempt to bring about a big, quick shift in sustainability. Focused largely on combating climate change and reducing human and environmental exposure to hazardous chemicals, the policy calls for generational changes in the bloc’s chemicals industry and numerous other sectors.

Due to the scope of rules and the speed at which they are being implemented, insiders warn they could cause drastic disruptions to industry, especially the chemicals industry, including lubricant additives. Not only could additional mandates pile atop companies, but new rules could hamstring the ability to use a number of materials on which lubricant companies depend, including lithium, chlorinated paraffins, alkyl phenols, polytetrafluoroethylene and compounds containing phosphorus.

“This framework is the mother of all regulatory frameworks,” Fuchs Petrolub Chief Technology Officer and executive board member Lutz Lindemann said Aug. 31 at Mineral Oil Technology Forum organized in Stuttgart by Uniti, the German association of medium-sized mineral oil companies. “The intent is good, the approach is good, but the regulation is very difficult and has potential to be terribly disruptive.”

He and others said the lubricants industry urgently needs to give feedback to politicians and regulators to try to avoid disruptions.

Adopted in 2020, the Green Deal was the EU’s overarching policy for achieving climate neutrality—reducing greenhouse gas emissions to levels that can be absorbed by natural systems—by 2050. In spirit it went beyond just meeting the region’s obligations for halting global warming, undertaking to lead the world in tackling the enormity of the problem. EU officials said the effort would set an example for the rest of the world. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called the Green Deal Europe’s “man on the moon moment.”

The Green Deal is wide ranging, calling for big rule changes in numerous areas. The chemicals industry is one of several receiving particular attention. It was only four years ago that the EU finished its 11-year phase-in of REACH, its landmark Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals law, deemed the world’s strictest chemicals regulation and the most complex law the EU had ever adopted. But leaders of the bloc are concerned that significantly more control is needed. A webpage about the EU’s chemicals strategy states that “most chemicals have hazardous properties which can harm the environment and human health” and cites predictions that global production of chemicals will double by 2030.

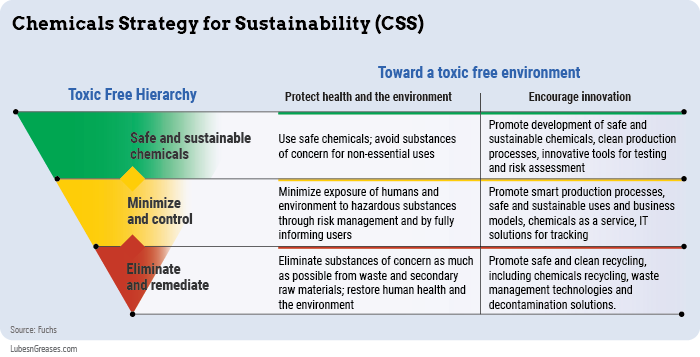

To address the perceived risks, the EU adopted in Oct. 2020 its Chemical Strategy for Sustainability, which seeks to phase out chemicals hazardous to humans or ecosystems while pushing industry to switch to materials that have lower carbon footprints. Many details must be fleshed out, but the initiative calls for the most harmful substances to be banned from consumer products and allowed elsewhere only when essential.

Whereas REACH evaluates the hazards of chemicals in isolation, the Chemical Strategy for Sustainability would account for the “cocktail effect,” which refers to additional hazards that can result from mixing chemicals. It also calls for banning the export of chemicals prohibited in the EU.

Under the Chemical Strategy for Sustainability, regulators are drafting a regulation named Safe and Sustainable by Design. It will aim to avoid undesired impacts of chemicals by requiring that aspects of sustainability be considered during product development. Those criteria would include whether a material will be hazardous, whether its supply is sustainable on a long-term basis, whether it can be supplied without hurting the environment, and whether the material may be collected and recycled after use.

The drive toward sustainability surpasses environmental issues to require adherence to social and corporate governance principles. Earlier this year the commission published a draft of a new supply chain law, including a directive for corporate sustainability due diligence, which would require businesses to find out if suppliers are using child labor or hurting biodiversity and to take action to halt those impacts.

The proposal would apply immediately to companies with at least 500 employees and worldwide annual revenue of at least €150 million and in two years would extend to those with at least 250 employees and revenue of at least €40 million. It applies to companies doing business in the EU regardless of where they are based and prescribes fines for violators.

The commission adopted the EU Taxonomy to direct investment toward activities that counteract climate change, sustainably use water and marine resources, and promote a circular economy.

The Green Deal also covers several other areas. For the energy sector it sets a goal of achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions—meaning all emissions would be offset by removal measures—by 2050. The policy includes general principles of shifting energy generation largely to renewable sources and of prioritizing efficiency, but specifics have yet to be laid out. Officials say they are drafting an update to the region’s energy taxation regime, which is expected to set higher rates for fossil fuels and give preferential treatment to renewables.

A biodiversity strategy calls for reversing ecosystem degradation, prioritizing those that can remove greenhouse gases. A section on buildings calls for requiring the construction industry to use more sustainable materials and would incentivize renovating existing structures to make them more energy efficient. For agriculture, the Farm to Fork strategy seeks to reduce use of fertilizers and pesticides, increase the portion of organic agriculture and reduce food waste.

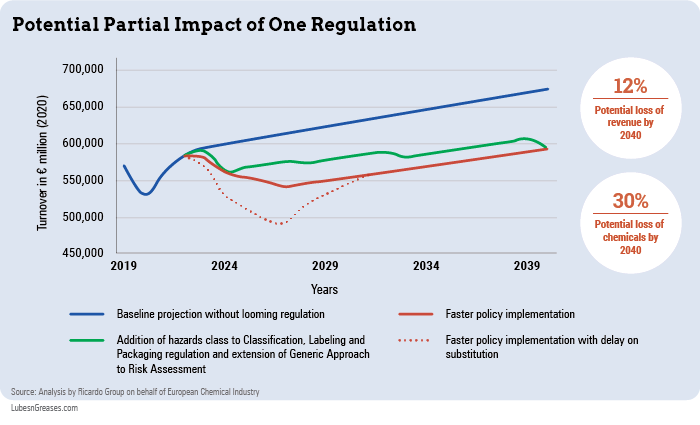

Lubricants and chemicals companies are raising alarms that these regulations could have drastic impacts on industry. The European Chemical Industry Council commissioned a study by British engineering firm Ricardo that assessed the impact of just two of the strategy’s actions—the addition of new hazard categories to the global harmonized system for Classification, Labeling and Packaging and the extension of the Generic Risk Approach for managing chemical risks.

The generic approach is one of two methods for determining if and under what conditions chemicals may be used and requirements for their handling, packaging and use. The generic approach automatically sets the same requirements for all substances with certain hazardous properties, as opposed to specific risk assessments, which weigh how the substance is used and specific exposure scenarios. As such, the general approach tends to result in greater restriction.

The CLP is a global system that sets standards for packaging hazardous chemicals and labeling that communicates those hazards and how to manage them.

Ricardo concluded that those two clauses could cause 30% of substances currently traded in the EU to disappear by 2040. It also forecasted that industry revenue would be 12% lower by that date than they would without implementation of the strategy. The firm predicted that revenues will sag more this decade and next and that the impact during the 2020s will be even more severe if businesses delay replacing substances that disappear from the market.

Lubricant industry insiders warn that the Green Deal and its various parts could disrupt use of several materials. Under proposed amendments to the CLP, lithium salts could be added to a list of substances of very high concern due to issues of reproductive toxicity, Lindemann said. This could restrict the use of lithium soap thickeners, which are used to thicken about 75% of the world’s industrial greases.

Lindemann cited several other materials that have been singled out for increased regulation or that he believed could be subject to the looming regulations. His list includes medium-chain chlorinated paraffins, which are used as extreme pressure additives in metalworking fluids; and alkyl phenols—a family of chemicals that includes alkyl phenate sulfides, which are key detergent additives and corrosion inhibitors in engine oils.

He said the regulations could also impact phosphorus-containing compounds, a number of which are used in lubricants and greases as anti-wear agents; polytetrafluoroethylenes, which are powders used as anti-wear additives but are also part of a family of the per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances that are under scrutiny around the world because of how they persist in the environment and accumulate in humans and animals.

Industry insiders said they are concerned not only because of the remarkably wide scope of the framework of regulations but also because of the speed with which the EU is proceeding. During a summer of extreme temperatures and growing evidence about the impacts of global warming, the sense of urgency seems to be accelerating.

In their public comments, sources within the industry seem generally supportive of the EU’s efforts, but they warned that some regulations could have unintended consequences that run counter to its goals. For example, if prohibition of certain additives reduces performance of lubricants, it could reduce fuel efficiency in applications in which they are used and lead to increased equipment damage and increased demand for raw materials.

“In the rush to reach worthy goals, we could cause developments that actually take us away from them,” Valentina Serra-Holm, president of the Union of the European Lubricants Industry, said Sept. 5 at the Lube Expo in Essen, Germany.

Industry sources are asking for relief from the pace at which new rules are being called for and implemented.

“The high number of simultaneous initiatives requires policy coherence and a sectoral approach with a clear roadmap and realistic timelines,” said Sabrina Stark, senior manager for sustainability and regulatory services at BASF, who also spoke at the expo. “We cannot do everything at the same time.”

All agreed that the industry urgently needs trade associations and other groups to coordinate to give the European Commission feedback about potential impacts of its actions so they may be tailored to minimize disruptions. This is a daunting task, they said, because of the scope of potential impacts, the amount of study required to assess them and the tight timeline for doing so.

“Policy makers need to understand the impacts of shutting off certain chemistries,” Lindemann said. “We have to raise our voices. Politicians must hear us and must understand us because these problems are complicated and they can be hard to understand.”

Tim Sullivan is base oil executive editor for Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Tim@LubesnGreases.com