After a tumultuous year in 2020, lubricant industry players may be wondering whether sustainability is still a priority in a post-COVID world. Independent sustainability expert and advisor Apu Gosalia posits that it is now more of a priority than ever, as sustainability can bridge the gap between recovery from the pandemic and innovation in the industry.

In his keynote presentation at the ICIS World Base Oil & Lubricants virtual conference in February, Gosalia cited a survey conducted by ICIS in January. The survey asked participants what they considered the biggest focus for the industry over the 12-month period following the survey. Sustainability was cited by 45% of the respondents, followed by recovery (39%) and innovation (15%).

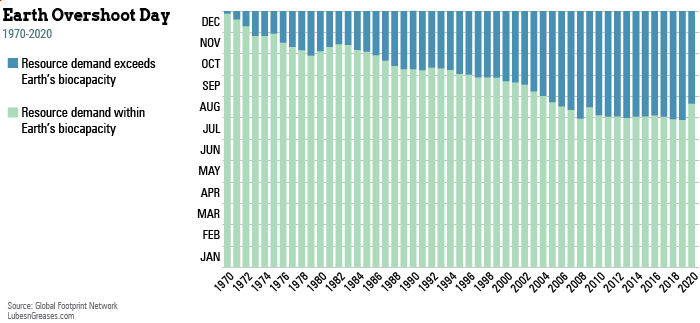

Furthermore, to set the stage for how critical sustainability has become, Gosalia explained the principle of Earth Overshoot Day, which is the calculated calendar date on which resource consumption for the year exceeds earth’s capacity to regenerate those resources in that particular year. “For the rest of the year, society operates in ecological overshoot by accumulating carbon dioxide in the atmosphere,” he said.

The first overshoot day occurred in 1970 on December 21, an overshoot of just ten days. In 2020, overshoot day came on August 22, an overshoot of 130 days. “This means that in 50 years the tipping point—where the resource demand exceeded the earth’s biocapacity—was pushed back by four months,” Gosalia said.

Sustainability Across the Board

Gosalia advises that to become sustainable, lubricant companies must first take a detailed look at each aspect of their processes, looking for ways to reduce their impact. “When you produce your lubricants, you need to ask yourself as a lube manufacturer, how sustainable is my production? How much energy and water do I consume while I make my lubricants, and what is the carbon footprint I leave behind? At the end of the day, my products must be sustainable at the customer application.”

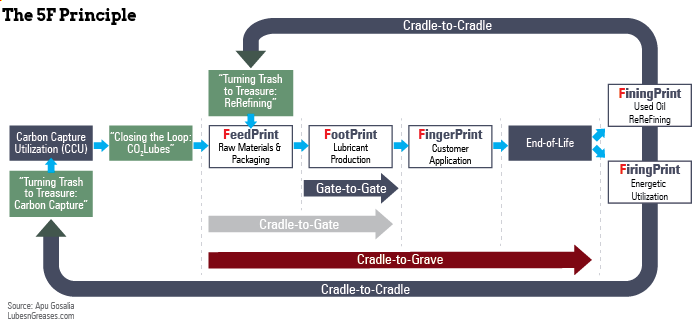

While this is a vital step, companies must also examine what comes before and after the blending process that may have an effect on the environment. This is known in life cycle assessment terminology as a cradle-to-cradle approach, which can be achieved by using what Gosalia referred to as the 5F Principle.

The first of the five F’s is the corporate carbon footprint, which is the impact of a company’s own lubricant production. This follows lubricants during the production phase, known as gate to gate.

|

“The name of the game is to work closely with your suppliers, so that they’re bringing the carbon footprint of their raw materials down.”

– Apu Gosalia

|

The second F is what Gosalia calls the feedprint, which follows lubricants from cradle to gate and requires companies to be mindful of the sustainability characteristics of its raw materials. “The question for a lube manufacturer at the end of the process and value chain is, where do I buy the raw material from?” said Gosalia. “How sustainable is my supplier? How sustainable is his supply?”

On the whole, lube manufacturers operate at the end of the value chain and have to bring in 100% of the raw materials to produce their lubricants. About 90% of the carbon footprint of a lubricant comes from the raw materials. “The name of the game is to work closely with your suppliers, so that they’re bringing the carbon footprint of their raw materials down,” he said.

Gosalia’s third F is the fingerprint—commonly called the handprint—which follows a lubricant from cradle to grave. “The fingerprint refers to the positive effects in customer application: the CO2 savings that a lubricant generates in customer operations. This can be calculated. If it is a specialized lubricant, it saves more CO2 in customer applications thanks to higher reduced friction and ability to protect against wear and corrosion compared to a conventional alternative such as a standard-type lubricant.”

The fourth F is the fining-print, a play on the word rerefining. To be completely circular, the end-of-life treatment of a lubricant product must be considered. “The waste oil that can be collected and rerefined into feedstock and ultimately become a new lubricant—and also the CO2 savings associated with that process—can be calculated,” Gosalia stated. “Here we are talking about cradle to cradle and circular economy.”

The final F is the firing-print, which refers to using oils that cannot be regenerated because of their high content of additives or pollutants being incinerated to generate power. At this point, CO2 is emitted again, but it can be captured, stored or utilized.

An example of carbon capture storage is a project being carried out in Iceland by CarbFix together with Climeworks, a Switzerland-based company. In this project, CO2 can be captured from emissions or directly from the air and converted into solid mineral rocks. According to Gosalia, “The method provides a complete carbon capture and storage solution where water with dissolved CO2 is ejected into sub-surface rock formations where natural processes transform CO2 into solid carbon and minerals within a couple of years. This process can be applied wherever favorable rock formations, water and a source of CO2 come together.”

Along a similar vein, a project specific to the lubricants industry—the CO2 Lubricants Project—was aimed at converting CO2 into lubricants. It was funded for nearly 2 million euros and carried out from 2016 to 2019 by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research in Germany and five other partners.

Gosalia summarized the project: Carbon dioxide was captured from industrial emissions or from the atmosphere and converted into lubricants using chemical and biotechnological processes. Various microorganisms such as yeast and algae use CO2 as a nutrient and can convert it into new products such as lipids. For the production of high-performance lubricants, these lipids are then extracted from the microorganisms and used either purely or in a further processed form. Microalgae fed with CO2 can achieve a lipid fraction of up to 80% of their weight.

“Thus, it is possible to capture the already-emitted CO2 and to either store it forever or utilize it to make a new feedstock for lubricants,” said Gosalia.

How else can sustainable solutions be applied to the lubricants industry? Gosalia stated that we cannot rely only on high-performance lubricants to reduce emissions in the use phase. “Working toward sustainability must be a three-step approach of calculating, cutting down and compensating for CO2 emissions that the lubricants industry generates. The first step is to calculate the corporate carbon footprint and the product carbon footprint.”

The next step is to search for opportunities to avoid and reduce CO2 emissions. “For instance, about 80% of the emissions of a typical lube manufacturer are caused by heat and electricity consumption, so energy efficiency is certainly an important lever in avoiding or reducing CO2,” Gosalia said.

Offsetting unavoidable carbon emissions through compensation measures is also critical to achieving carbon neutrality. Since emissions impact the climate at a global level, it is ultimately irrelevant where on the planet they originate and where they are saved, Gosalia stated. Compensation measures occur through the voluntary promotion and investment in climate protection projects in socially, politically or economically disadvantaged countries. Typically, projects used for compensation measures target six project sectors: biomass, cookstoves, solar energy, forest conservation, hydropower

and wind energy.

European Green Deal

Complying with new legislation is another way that lubricant companies can shape their sustainability strategy. “Sustainability is a solution in times of uncertainty,” said Gosalia. “There is an additional strategic opportunity opening up, especially in Europe with the European Green Deal.”

The European Green Deal is a wide-reaching package of legislation that aims to make Europe the first climate neutral continent by 2050 and support industry to innovate and become global leaders in the green economy.

There are numerous measures and initiatives alongside the Green Deal. One of these is the Circular Economy Action Plan, which tackles waste prevention and reduction. These increase the recycled content along the entire lifecycle of products in order to modernize and transform the economy while also protecting the environment.

Gosalia stated that “the European Green Deal opens the age of circularity and recyclability, urging companies to make sustainable products and reduce waste while making them.”

However, as the world has become increasingly globalized, the deal will require global buy-in, Gosalia predicted. Fortunately, countries around the world are beginning to take the necessary steps. On April 21, the EU Council and the European Parliament reached a provisional agreement setting into law the objective of a climate-neutral EU by 2050 and a net greenhouse gas emissions reduction target of 55% from 1990 levels by 2030.

Additionally, President Biden hosted a virtual Leaders Summit on Climate on April 22 and 23 to catalyze global ambition to address the climate crisis. The summit convened world leaders to galvanize efforts to keep the goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius within reach.

“The spring of 2021 was a period of cosmic significance for sustainability,” Gosalia emphasized. “Economic policy measures should be closely linked to overcome both the climate crisis and the COVID crisis at the same time, and sustainability bridges the gap. For sustainability, only the sky is the limit.”

Sydney Moore is managing editor of Lubes’n’Greases magazine. Contact her at Sydney@LubesnGreases.com.