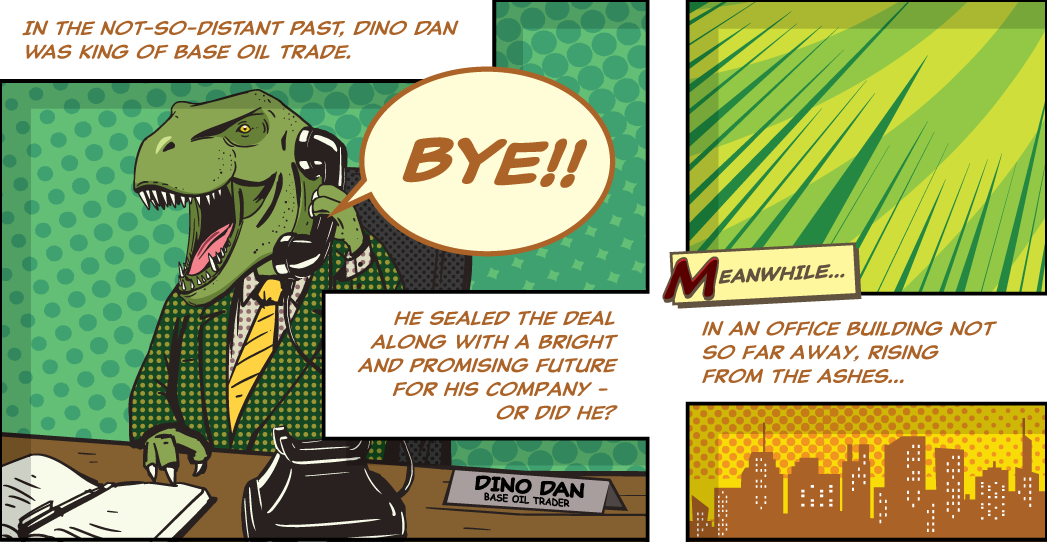

Are base oil traders being edged out of the lubes industry?

Traders have played a long and storied role in international commerce, dating back to when countless merchants made their livings on the Silk Road connecting sellers of leather, silk, paper, spices and gunpowder in regions like China and the Middle East to buyers throughout the Roman Empire and elsewhere in Europe. A small, modern-day part of that tradition, base oil traders have long been key players in the lubricants industry.

However, with recent advances in technology and communications, in addition to market disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it appears that some traders are being pushed out. In fact, Joe Rousmaniere, director of business development for Chemlube International, has even speculated that a “permanent extinction” of many trading companies may be looming on the horizon.

Dinosaurs or Phoenixes?

According to industry consultant Geeta Agashe, there are five key reasons that base oil traders were able to survive and thrive in past years, the first being that base oil refiners often did not know enough about customers’ needs and preferences outside of those in their home market. “Traders typically have ‘feet on the street’ and know the final end-use customer well, as well as their requirements, so they possess critical local market intelligence,” she said.

Conversely, traders also sourced base stocks for the end-use customer from refiners with whom the buyer had little to no knowledge or experience.

Third, traders assumed much of the risk associated with getting product to its final customers; they provided safe transport, handled logistics and made sure that products cleared customs. They also ensured that the refiner was paid for their base stocks.

Fourth, traders created small and special blends for their customers based on their exact specifications, while refiners could not be as flexible.

Fifth, some traders had storage capability as well as their own deep-water terminal facilities and relationships with ocean-going tankers.

With some on the rocks right now, it is unclear whether modern base oil traders can succeed in the lubes industry by filling these same roles.

An example of a trader that has been in the woods in recent months is Gulf Petrochem. Rumors circulated around the industry that the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent business slowdown had forced them to stop some operations. In a July 20 press release, the company sought to dispel what it called “factually inaccurate information.” However, GP did admit that it has struggled to secure credit from several institutions and has “undertaken a financial restructuring exercise” but continues to make trades in the meantime.

So, are all of today’s traders doomed for extinction, or will the majority rise up from the ashes of a struggling market to redefine their role within the industry?

The evolution of the lubricants industry has made the traders’ role a smaller one that is more easily absorbed by buyers and suppliers. In an increasingly globalized market, suppliers are better able to keep tabs on which companies need to buy which base stocks around the world.

One former base oil supplier who asked not to be named said he gauged his business’ success by whether or not he had to employ the help of traders. “When we had to use them, I felt we failed in our ability to properly predict our supply and demand. Unless the traders found value-add business, which was very rare, they were considered my lowest value price tier and the sale I wanted to eliminate.”

|

“It can be assumed that everyone knows everything. So, specialized market knowledge is becoming less of a factor.”

– Geeta Agashe

|

Rousmaniere agreed, explaining that there is less room in the industry for traders now because they do not add as much value as they used to. “In the past, a large part of traders’ value was that they knew who needs what and could place excess barrels with buyers. That knowledge is, for the most part, commonplace amongst industry players now.”

Agashe asserted that one reason for regional market knowledge becoming more widespread has to do with the plethora of yearly base oil conferences and the global dispersal of lubricant industry publications and data. “It can be assumed that everyone knows everything. So, specialized market knowledge is becoming less of a factor.”

Similarly, she expressed concern about some of today’s traders becoming too reliant on a specific country market for supply or for customers. When a particular market dries up or becomes too saturated, traders are forced to scramble for business, and some never recover.

Shipping services were another a unique benefit traders offered, and many still do. But now major companies are more able to provide their own shipping services, Rousmaniere said.

Another nail in traders’ coffin is the growing demand for base oils that carry engine oil approvals. Fewer buyers find it sufficient to purchase generic specification base oils, while more demand that the base oils they purchase must be sourced from a particular refinery in order to meet mandated approvals, Agashe explained. “Traders play a greater role where markets are less discriminating in quality selection.”

A better fit for today’s market and into the future may be certified distributors, said the former base oil supplier, a prediction that Agashe seconded. “As formulation approvals play an increasing role, the traders’ role will be replaced by distributors that supply approved base oils,” she explained.

Liang Hua, sales manager for Luhua Petrochemical in Linyi, Shandong province, China, agreed. “Clients will not be willing to pay extra money to buy Chinese-produced Group III oils. They will need to see some kind of certification to prove the quality, but Chinese refiners don’t offer such a certification.”

Traders have also failed when key personnel have retired or left the companies at which they previously worked and the new staff were not as effective in maintaining existing customers, Agashe said. “It is a very tough business these days, and unfortunately we feel there will continue to be shutdowns of many traders active in this space.”

Survival of the Fittest

On the other hand, despite the hurdles that exist, many traders seem to have figured out how to survive in today’s tricky market.

Agashe explained that “traders will continue to add value primarily in risk assumption and logistic support. One important new development that is playing an ever-larger role in the industry is the shipment of base oils in flexitanks. The use of these flexitanks vastly increases market reach but at the expense of requiring a massive amount of hands-on logistic support. Large base oil refineries are reluctant to take on this logistical burden, which is increasingly undertaken by traders.”

Denis Varaksin, managing director of Berlin, Germany-based trader DYM Resources, agreed that traders do and will continue to provide invaluable shipping services. “DYM Resources buys from Russian refineries in rail tank cars, accumulates product in different ports and sells product to clients in flexitanks, rail tank cars, trucks, iso-tanks or bulk [containers]. There is no refinery that could offer the same range of grades, financial flexibility and modes of transport at the same time.”

|

“Unless you have a very, very solid risk program, you’re in jeopardy.”

– Joe Rousmaniere, Chemlube International

|

Being a successful trader, said Varaksin, also requires thorough knowledge of the product being sold and its technical applications. “We also regularly improve our technical expertise to advise which raw materials would work better in certain applications. Good traders advise their customers when it is a good time to buy base oil to avoid shortages before upcoming maintenance [turnarounds] or other disruptions.”

The remaining value provided by traders is financial protection, according to Rousmaniere. When dealing in shaky places like Mexico, Nigeria and Indonesia, suppliers can be exposed to significant financial risk, and the same is true for traders. “Unless you [traders] have a very, very solid risk program, you’re in jeopardy.”

Traders assume risk from both the refiner and from the end users, Agashe elaborated. “Very few refiners are willing to sell beyond FOB refinery and are loathe to offer extended payment terms beyond line of credit payment. Many end users demand extended payment terms and will demand that quality received in their plant be as guaranteed. The trader provides great value to both buyer and seller by assuming the risk of both payment and quality assurance.” FOB stands for “free on board” or “freight on board” and means that the refiner incurs no costs after the base oil leaves its gate.

While it is difficult to predict the fate of base oil traders, it is more certain that traders will need to adapt to the changing market if they hope to still be a prominent part of it.

Liang admitted that doing business has become increasingly difficult for his company. “I’m not too optimistic about the [base oil trading] business, at least not in the next two years. People in the business I know are all struggling or thinking about doing new businesses.”

More specifically, Liang noted that reduced prices for base oils have forced Luhua to reconsider its trading methods. “The average price of Group II oils has dropped about ¥1,500 (U.S. $216) per ton in the past seven months, which caused a big loss for many base oil traders. I don’t think [Luhua’s] role as a base oil trader will change, but one thing I’m sure of is that we will face more pressure on pricing. So we will have to find more decent oil sources with lower prices.”

Luhua, which currently trades mostly Group II base stocks, has considered the possibility of changing the types of base stocks it trades as well. “We actually thought about [trading Group III oils] because it’s well known that Group II oils are oversupplied in China, and the competition is fierce.”

Fortunately, Agashe assured there are traders that have been able to evolve along with the rest of the industry, ensuring that they not only survive but flourish. “Many traders have thrived in this changing environment by getting into integration plays and minimizing risks. For example, Chemlube also produces finished lubricants, which is a forward integration play. Some traders have taken financial stake in base oil refineries, which is a backward integration play and ensures availability of product. Others have invested in transportation and logistics. Some have created market intelligence reports for their suppliers.”

Sydney Moore is assistant editor for Lubes’n’Greases magazine. Contact her at Sydney@LubesnGreases.com.

Wang Fangqing contributed to this story.