African countries account for just 1% of global new car sales, and in the past making vehicles there has been no easier than selling them. In fact, it has been a “monumental failure,” said Volkswagen Group South Africa’s CEO, Thomas Schafer, in an article published by the Economist.

During an October 29 interview for that article, Schafer said that VW is now trying again in as many as five African countries, and it isn’t alone; executives with Ford, Toyota, Suzuki, Nissan and others are signing deals and starting assembly lines across the continent. VW’s current plant in Rwanda has capacity of up to 5,000 vehicles per year, and Ford’s facility in Nigeria is comparable.

The results of these expansion efforts will help to shape global lubricants trends in the coming decades.

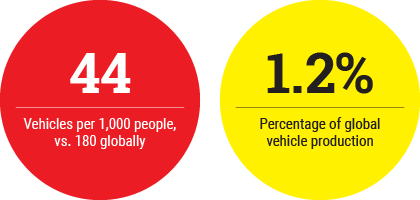

According to a study published by consulting firm Deloitte Africa, the continent’s motorization rate was 44 vehicles per 1,000 people in 2015, a clear contrast with the global average of 180. But the United Nations says it has the fastest population growth and urbanization rate of any continent, and increased political stability since the end of the Cold War has brought economic growth. For an emerging middle class, cars have become increasingly affordable.

“Demand for energy is increasing at a much faster pace in Africa than in other regions of the world,” said Rakesh Vyas, a market development advisor for ExxonMobil. “Car ownership and motorization rates are skyrocketing.”

There are multiple ways this surge in transportation demand can be satisfied, each solution having different implications for lubricants. Africa’s current system relies on importing used vehicles. This method dictates that lubricant demand will follow the speed at which these aging options are displaced by new cars or younger imports.

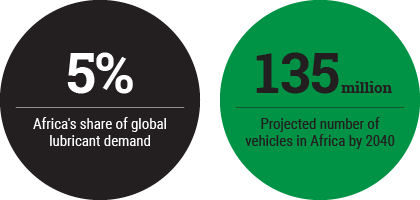

Precise figures for Africa’s vehicle stock and lubricants markets aren’t always reliable, as data-gathering efforts vary by country. However, according to the U.N., the continent accounts for about 1.2% of global vehicle production and 5% of global lubricants demand. In 2018, the total vehicle count was about 45 million, and that amount could triple in the next 20 years, according to the United Nations Environment Programme.

New vehicles represent a small share of the overall market. In Nigeria—Africa’s largest economy and home to roughly a fifth of its people—for every new car sold in 2017, there were 131 used car sales, according to UNEP. Vehicle demand is typically met by imports of used light-duty vehicles from the United States, Japan and Europe.

Lubricants demand in Africa is expected to rise by about 13% from 2020 to 2025, from about 1.7 million tons to 2 million, according to forecasting by ExxonMobil’s Vyas. Global demand is expected to grow about 2% in that same period. Lubricant blending capacity is on the rise on the continent, but new facilities in countries including Kenya, Cote d’Ivoire, Tanzania and Uganda complement existing ones in the automotive assembly hubs, said Siva Konar, Lubrizol Corp.’s managing director for Africa.

Demand for API Group I base oils will increase by 6% in Africa, against a 16% drop worldwide said Vyas. There are six African base oil production sites: four in Egypt, and one each in Algeria and South Africa, but the continent is expected to remain a net importer of base oils for the foreseeable future, said Unathi Fani, automotive products manager at South Africa’s Engen Petroleum.

According to the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers, South Africa and Morocco accounted for 92.9% of vehicles produced on the continent in 2019. However, the manufacturing process utilized in Africa is typically one in which semi-complete or complete knockdown kits are shipped to sites, often with the engines already filled with lubricants. In South Africa, the goal is to boost local content of the finished autos from 38% in 2018 to 60% by 2035, according to consulting firm TechSci Research.

Assembly elsewhere on the continent is typically limited to small-scale operations such as VW’s plants in Kenya and Rwanda, but production is ongoing, planned or under consideration in Egypt, Algeria, Nigeria, Ghana and Ethiopia.

Policy is Pivotal

Government policies on vehicle and fuel standards will also shape the future of lubricant supply, production and demand. One of the main variables these policies control is the age of used imports. Half of Africa’s 54 countries have no maximum age for used imports, but the countries with the largest economies do. In South Africa, Morocco and Egypt, used imports are banned. In six of Africa’s top ten economies—Algeria, Angola, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania and Ghana—the maximum is between three and 12 years.

During the ICIS African Base Oils & Lubricants Conference in November, Vyas noted that Ethiopia has the ninth-largest economy and no cap on used imports. The country also stands out because its motorization rate is far lower than other countries, with only two vehicles per 1,000 people. In comparison, Kenya has 28 vehicles per 1,000 people, and Nigeria has 20, according to Deloitte.

Governments across the continent are offering a combination of tax breaks, caps and tariffs on imports, and other incentives. In return, they expect job creation. Ghana, where VW, Suzuki, Toyota and Nissan have signed memoranda of understanding, offered 10-year tax breaks and to boost duties on imports to 35% from the existing range between 5% and 20%, according to Bloomberg and Nigerian news source BusinessDay.

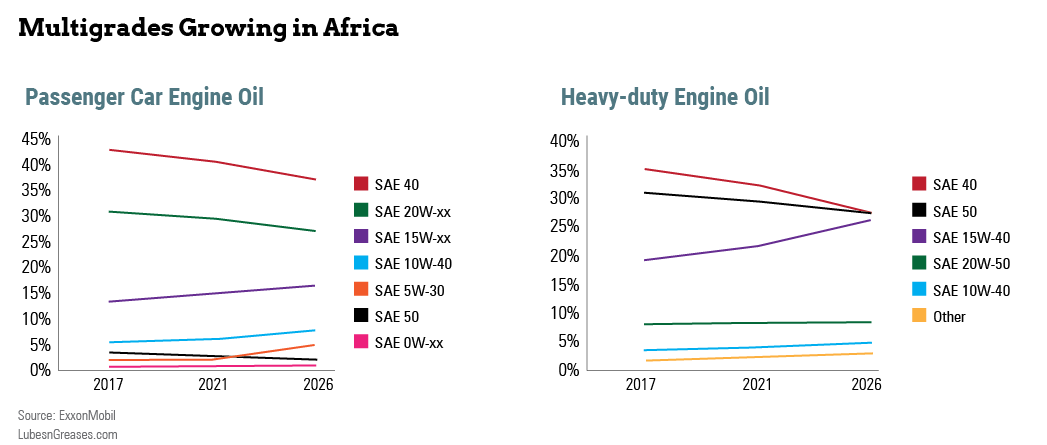

As vehicle stocks get younger, it is more important to ensure appropriate lubricants are used. “Today you might find a car that’s five to eight years old filled with lubricants meant for a vehicle that’s 12 to 15 years old, hence the need for higher-performing lubricants,” Lubrizol’s Konar said.

This is one reason why vehicle maintenance is difficult, said Patrick Swan, principal at Aswan Consulting in Cape Town, South Africa. “People expect vehicles to last as long as they do elsewhere, but the operating life is generally less than in Europe or the U.S.A.”

In the global automotive aftermarket, Africa accounted for about $3.68 billion of the $33.17 billion total in 2018, according to TechSci Research. The figure is expected to grow to $5.42 billion by 2024, or 11.36% of the total $47.73 billion market.

Counterfeit lubricants—typically just base oils without additives—are another variable, Engen’s Fani said. “Governments and lubricants suppliers need to do more to ensure consumers are educated on the benefits of buying quality lubricants,” she urged.

For factory-fill lubricants, it’s not yet clear that more domestic automotive production in Africa would help drive the adoption of newer lube alternatives because lubricant producers tailor production to existing standards. Kenya, for example, planned to adopt Euro 4 emissions standards, but the Kenya Motor Industry Association asked for extra time to comply. The group instead proposed moving to Euro 2 by 2021 and Euro 4 by 2024, Rita Kavashe, chairperson of KMIA, told Business Daily.

In March, before the coronavirus pandemic, African governments were moving to implement the landmark African Continental Free Trade Area, which will create the largest free-trade area since the formation of the World Trade Organization. Zero-tariff trade was to have begun by July 1, but implementation was delayed in April. A new start date had not been set at the time of writing.

“What we envision is a hub-and-spoke model, with regional supply chains,” said Dave Coffey, CEO of the newly-formed African Association of Automotive Manufacturers. “Some countries could be manufacturing hubs, and in others, parts suppliers would emerge.”

While negotiations of tariff lines and exemptions were ongoing before the pandemic halted progress, it was expected that vehicles assembled in Africa would be considered domestic goods as long as they included at least some local content from African countries, said Komi Tsowu, an economist for the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

For lubricants, he said, once negotiations are complete, the deal could allow blenders to import base oils and export to the region without paying the tariffs, giving them a leg up on importers of finished products. This already happens on a smaller scale in a regional trading bloc for 13 southern African states that are members of the Southern African Development Community. Blended lubricants with at least 40% local content are exempt from import tariffs of up to 10%, said Konar.

For now, as governments and executives work to uncover the best conditions for investment, production, jobs and growth, lubricants producers are working to cut deals and boost capacity. Storage facilities in South Africa and Morocco are expanding, said Cliff Classen, business manager for lubricants and specialities for South Africa’s national oil company, PetroSA, and former CEO of Orbichem Petrochemicals, a South African base oils importer.

In Nigeria, a recent deal saw GP Global, a United Arab Emirates-based lubricants supplier, acquire Lagos-based blending, distribution and marketing operation Grand Petroleum, its third acquisition in Africa since 2014. Other recent investments include France’s Total SA investing $20 million in a blending plant in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and China’s Sinopec entering the Kenyan market via a distribution agreement with Nairobi-based marketer Bitutech Ltd.

Electric or ICE?

While policy moves may dictate immediate changes for the African automotive lubricants market, electricity supply could determine the speed at which Africa moves away from Group I-based lubricants. According to the U.S. Agency for International Development, roughly two-thirds of Africans lack access to electricity, meaning that a widespread transition to electric vehicles is less likely on the continent.

This is an important distinction for the lubricants industry because EVs, as they evolve, are expected to require fewer but more expensive lubricants. Without enough electricity and slow development of charging station networks, African demand for internal combustion engines could provide a buffer against the slow-moving global disruption to the lubricants industry that EVs present. Currently, only South Africa offers a network of charging stations to facilitate long trips in EVs, and import duties on EVs are higher than for ICEs, Fani said.

For now, hybrid cars are a better fit for Africans seeking low-emissions vehicles, but global trends could also change Africa’s market. “What happens elsewhere could shape supply for Africa, and we may have to switch over,” said Classen. “If the rest of the world switches to EVs, I can’t see automakers going to dual assembly lines in the long term so that they can still make internal-combustion cars for Africa.”

Matt Mossman is a global economics writer and consultant based in Washington, D.C. Contact him at mm@mattmossman.com.