Crunch Time

Looking at the United States lubricants business today, it’s hard to believe that just two decades ago there were close to 10,000 lubricant distributors in the U.S., and each major had contracts with up to 1,000 distributors. It seems almost unfathomable by today’s metrics that a lubricant distributor with annual sales at 1 million gallons was considered large and that less than a handful topped 5 million gallons in the 1990s.

A lot has changed over the past 20 years. Today, many even question the viability of a 1 million-gallon distributor, and some of the largest are moving over 50 million gallons annually and growing.

Much of the change in the distributor landscape was the result of consolidation among the majors in the 1990s. Due to brand and channel conflicts as well as redundancies in the distribution networks born from the merger and acquisition activity during that time, majors consolidated their distributor networks. In doing so, they focused on those considered most successful that aligned with their brands. This significantly culled the number of distributors in the business by driving exits and acquisitions.

But while the redundancies created by majors’ M&A activity can be attributed to the start of distributor consolidation, it didn’t end after the last melding of majors came in 2005.

As painful as consolidation was to the many casualties of the process, the benefits were clear. In addition to reduced supply chain cost, improved efficiency and accumulated sales and technical expertise among distributors, it provided majors with an opportunity to significantly reduce customer acquisition cost and rapidly grow market share. Simply stated, it typically costs significantly less for a major to encourage its distributors to grow its brand by acquiring the competition and converting those brands to the ones the distributor sells than it costs to grow organically.

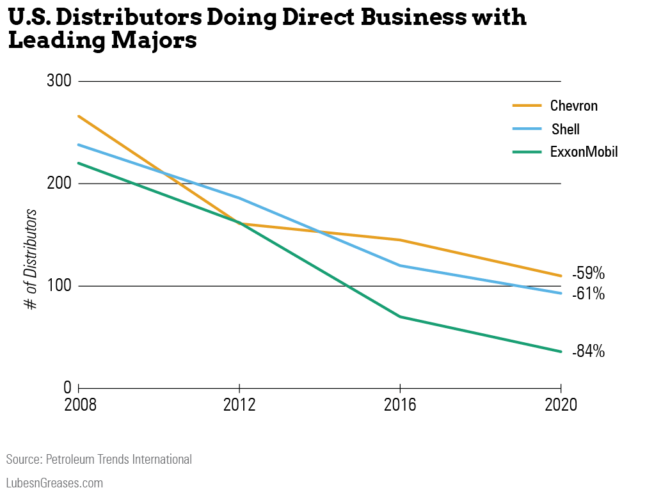

Whereas the majors used both sticks and carrots to encourage distributors to grow through acquisitions, the message was clear: Either grow—and fast—or go. So, the race was on, and the numbers tell an interesting story. In looking at the three largest majors in the U.S. lubricants business, Chevron reduced the number of distributors with which it does direct business by 59% from 2004 to 2020, Shell by 61% and ExxonMobil by 84%.

Where ExxonMobil had about 300 distributors, including close to 50 that handled only packaged lubricants in 2004, it currently has just under 40 covering 50 states. Some of the largest with multistate coverage include PetroChoice, Brenntag Lubricants, Keystops, Parkland and McPherson.

Chevron had close to 550 lubricant distributors in the U.S. at the start of this millennium, and today that number has been reduced to a little over 100. Some of the largest with multistate coverage include RelaDyne, Pilot Thomas Logistics, Prime Lube, Hampel Oil, Parman Oil, Senergy Petroleum, Shrader Tire & Oil and Shoco Oil.

Although Shell started 2004 with significantly fewer distributors than Chevron, today it has only about 20 fewer. Some of its largest distributors with multistate coverage include Dennison, Engelfeld Oil, PPC, O’Rourke Petroleum, Van De Pol Petroleum, RelaDyne, Posinello Fuels, Taylor Enterprises, Allied Oil & Tire and Keller-Heartt.

There has also been a marked reduction in the number of distributors doing direct business with two of the leading majors at the same time. Although many still carry other brands and are growing their private label business, the degree of alignment is remarkable. When combined, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Shell have direct relationships with close to 250 distributors, and only about 10 are split between brands. Among those, nearly all are shared between Chevron and Shell.

Importantly, even though the number of distributors doing direct business with the leading majors has dwindled, many of the smaller marketers continue to sell these majors’ brands. This is because instead of simply cancelling contracts and walking away, as was often the case in the 1990s, majors recognize that many of the smaller distributors are still viable and important to their brands.

So, rather than leaving them scrambling to find another brand or shutting the doors, some are given the opportunity to continue selling the brand they have been championing for years by way of signing on as associates or sub-distributors. But instead of having a direct contract with the major, they have a contractual relationship with the major’s authorized or master distributor in their region.

This creates an interesting dynamic that shifts the burden of responsibility and the cost of managing smaller distributors from the major to its master distributors, while at the same time reducing the risk of losing market share to competition picking up the major’s orphaned distributors.

So, although the numbers have been markedly reduced and there is not much headroom left for more consolidation, some distributors will be forced to make high-stakes decisions about the majors with which they align and the brands they carry moving forward.

And it’s not just about the big three majors in terms of volume. Distributors must also consider the impact their decisions have on their representation and sales of such marquee brands as Valvoline and Castrol and the highly recognized brands of Philips 66 and Citgo. Adding to that, a number of the larger distributors have well-respected and growing brands of their own to consider.

With that, it’s likely we will see some unexpected changing of the guard in which brands some of the big distributors in the business continue to carry.

Tom Glenn is president of the consulting firm Petroleum Trends International, the Petroleum Quality Institute of America, and Jobbers World newsletter. Phone: (732) 494-0405. Email: tom_glenn@petroleumtrends.com