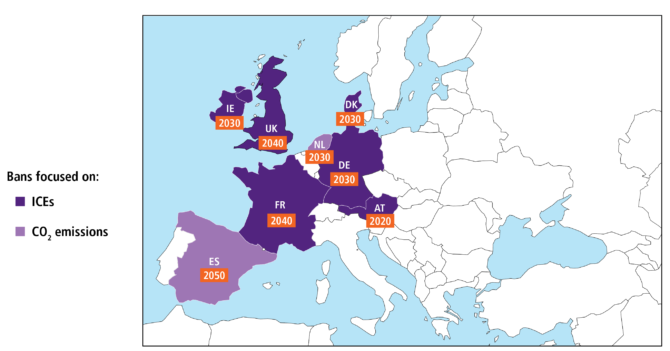

Bans on internal combustion engine vehicles are gradually sweeping across Europe. Their practicalities are a point of discussion ahead of implementation.

On Nov. 13, the administration of Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez published a proposal for several measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including one that would prohibit – beginning in 2050 – sales of cars or light-duty trucks that emit carbon dioxide.

A month earlier, Denmark’s Prime Minister Lars Lokki Rasmussen called for a 2030 ban on sales of new cars that run solely on petrol (gasoline) and diesel, and for that ban to be extended to hybrids in 2035.

These announcements brought to eight the number of European countries that have proposed or adopted such bans. Both types of mandates are viewed as policies that could forcefully shift car populations to electric power – and thereby reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Analysts agree that such policies will be effective if implemented but maintain that it is too early to say if they will be.

Electric vehicles receive a lot of coverage these days from traditional news organizations as well as newsletters and blogs focusing specifically on the auto industry or environmental issues, not to mention non-profit groups promoting cleaner transportation. It is easy to find lists of European countries with some sort of plan to ban cars that use fossil fuels or that emit CO2. Austria, Ireland, France, the United Kingdom and Germany join Denmark in the focus on getting rid of internal combustion engines, while the Netherlands, like Spain, takes direct aim at CO2.

But these lists often fail to explain that at least some of the bans have not been approved by all necessary branches of government. For example, the proposals in Denmark and Spain would both require parliamentary assent. The prime ministers in both countries said they would seek such approval in coming weeks.

In some other countries, there seems to be less movement. Germany’s Bundesrat, which represents the nation’s 16 states, called in October 2016 for the country to ban registrations of ICE-powered cars beginning in 2030. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government has made no movement to take up the issue, though in October it did propose a package of clean transportation measures aimed at discouraging local bans on diesel cars.

A number of German cities enacted such bans after a lawsuit by a civil society organization complained that they were violating European Union limits on nitrous oxides. Critics called the central government’s solution a set of half steps more concerned with appeasing the nation’s auto industry.

Austria’s Environment Agency published a plan in 2016 to ban sales of new ICE-powered cars beginning in 2020, but there is no sign of the rest of the government taking up the issue. The agency did not respond to questions from Lubes’n’Greases about the status of the plan. The Netherlands’ ban was part of a government accord published by coalition partners after the nation’s most recent general election in 2017. No further action has been taken though, and the government is still described as “striving” toward that goal.

Ireland has scheduled a ban on ICE cars to begin in 2030. The U.K. and France agreed to do likewise in 2040, although Scotland, which has semi-autonomy within the U.K., has its own ban slated for 2032.

|

“The auto industry here is very powerful because it’s such a large part of the economy. But you also find opposition from workers who oppose actions that could eliminate jobs.”

— Sophia Becker, Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies

|

While EV proponents would like to see the bans enacted, observers say pushback should be expected from the general public, at least in some countries.

“I’m quite sure there is no political will for this in Germany,” said Sophia Becker, a research associate with the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies in Potsdam, Germany. “The auto industry here is very powerful because it’s such a large part of the economy. But you also find opposition from workers who oppose actions that could eliminate jobs.”

Denmark’s Rasmussen acknowledged the challenge in his Oct. 2 speech to parliament. “It is a big ambition that will be hard to achieve,” he said. “But that’s exactly why we need to try.”

Observers said the fates of the bans proposed to date will likely vary – that some may be implemented on schedule while others get delayed or dropped for the foreseeable future.

“I think the countries like France and the U.K. really want to adopt a ban, but in the end they may postpone it a bit,” Becker said. “France has a more centralized government than Germany and an abundance of nuclear energy, so I think the transportation transition will be easier there.”

Some have questioned the commitment of European governments, pointing to the fact that none of these bans has taken effect, and some are not scheduled to do so for decades. Others argue that governments are already taking other steps to promote EVs. Like many nations, the eight mentioned above shell out money in the form of subsidies and tax breaks for EV purchases.

Incentives get credit for helping Norway become the world’s capital in terms of both penetration and number of EVs per capita. Hybrids and BEVs accounted for 52 percent of new car sales in the country in 2017, and it now has 21.5 plug-in EVs per 1,000 people. The Norwegian Parliament has set a goal of only zero- or low-emission new vehicle sales by 2025 but stated that it aims to accomplish that without prohibiting ICE vehicles.

The cause for boosting use of EVs is using some sticks, along with carrots. The EU, like the United States and China, has encouraged automakers to increase EV sales by offering credits that help them meet fuel economy and emissions standards – standards that impose expensive penalties if companies exceed mandated limits.

But those pushing for big reductions in greenhouse gas emissions may continue calling for bans on conventional vehicles. In an October briefing, the International Coalition for Clean Transportation said the current regulatory approach is not reducing CO2 emissions fast enough to meet 2050 goals set by the Paris Agreement. The organization, which is based in Washington, D.C., advised that governments will need to require zero-emission vehicles in order to meet those goals.

“Efficiency standards are essential but insufficient to launch a mainstream electric vehicle market,” the ICCT said in its briefing. “Ensuring the transition to electric by 2050 means much bolder efficiency standards or direct electric vehicle requirements are needed.”

If that sentiment proves popular, then governments should continue to hear calls for bans on ICE cars.

Canada Ups its EV Game but Still Lags Climate Change Goal

British Columbia’s Premier John Horgan said in November that his government would introduce measures requiring all new light-duty vehicles sold in the province be electric or zero-emissions by 2040.

The target, which will enter into law in early 2019, will be achieved in phases, starting at 10 percent by 2025, 30 percent by 2030 and 100 percent by 2040. The province will also increase the number of fast-charging points and offer incentives worth around U.S. $3,780 to each person who buys a hybrid or battery electric vehicle.

Even though the western Canadian province set aside $53.6 million for its Clean Energy Vehicle Program – a package of incentives, infrastructure investments, research and training initiatives – ZEVs only make up 1.5 percent of vehicles on the province’s roads, according to Canadian media. B.C. has 746 charging stations with 1,485 Level 2 and DC fast-charging outlets. The country has 3,752 stations with 7,116 outlets.

In 2017, EV sales across Canada as a whole accounted for 1 percent of new vehicle sales, but they increased 214 percent in the second quarter of 2018, year-on-year. However, according to the Sustainable Transportation Research Team at B.C.’s Simon Fraser University, no Canadian province is on track to reach the IEA’s policy goal of 40 percent EV market share by 2040 to mitigate climate change. “More stringent policies are needed,” it found. STRT produces transport industry research and awards provinces grades for their progress in EV acceptance, business and innovation strategy and public support policy.

Dan Woynillowicz, policy director for Clean Energy Canada, agreed.

“There is a patchwork of sub-national efforts to encourage EV adoption, concentrated in the provinces of Quebec and British Columbia – and until recently, Ontario, where the recently elected conservative government rolled back EV policies,” he told Lubes’n’Greases. “But other than investing in EV charging infrastructure, the federal government has done relatively little and has yet to adopt any of the key policies needed, such as purchase incentives or a zero emission vehicle mandate.” Clean Energy Canada is a think tank that also is within Simon Fraser University.

Sorry, a technical error occurred and we were unable to log you into your account. We have emailed the problem to our team, and they are looking into the matter. You can reach us at cs@lubesngreases.com.

Click here link to homepage